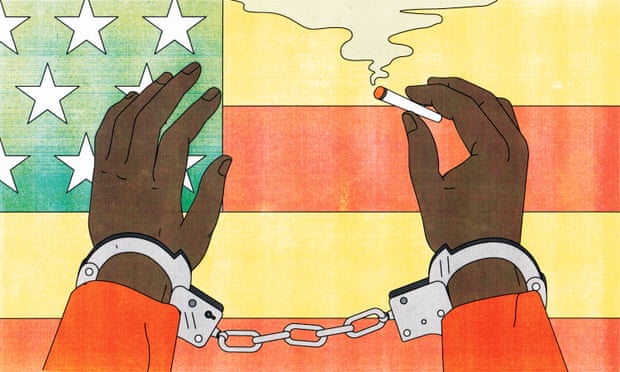

Racist Roots of the War on Drugs

Racist Roots

"As marijuana arrests disproportionately affect minorities, controversy grows over a term prohibitionists hoped would appeal to xenophobia

It’s been known as dope, grass, herb, gage, tea, reefer, chronic. But the most familiar name for the dried buds of the cannabis plant, and one of the few older terms still in use today, is “marijuana”.

For the prohibitionists of nearly a century ago, the exotic-sounding word emphasized the drug’s foreignness to white Americans and appealed to the xenophobia of the time. As with other racist memes, a common refrain was that marijuana would lead to miscegenation.

Harry Anslinger, the bureaucrat who led the prohibition effort, is credited as saying back then: “There are 100,000 total marijuana smokers in the US, and most are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos and entertainers. Their Satanic music, jazz and swing result from marijuana use. This marijuana causes white women to seek sexual relations with Negroes, entertainers and any others.”

Halperin, A. (2018, January 29). Marijuana: Is it time to stop using a word with racist roots? The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/jan/29/marijuana-name-cannabis-racism.

"Marijuana: is it time to stop using a word with racist roots?" -by Alex Halperin

Article Continued

Today “cannabis” and “marijuana” are terms used more or less interchangeably in the industry, but a vocal contingent prefers the less historically fraught “cannabis”. At a time of intense interest in past injustices, some say “marijuana” is a racist word that should fall out of use.

Harborside, which is among the oldest and largest dispensaries in California, says on its website: “‘Marijuana’ has come to be associated with the idea that cannabis is a dangerous and addictive intoxicant, not a holistic, herbal medicine ... This stigma has played a big part in stymying cannabis legalization efforts throughout the US.”

It’s clear why a business like Harborside would prefer the more scientific word for branding purposes, but does that mean everyone should follow along?

The word “marijuana” comes from Mexico, but its exact origins remain unknown. According to the book Cannabis: A History by Martin Booth, it may derive from an Aztec language or soldiers’ slang for “brothel” – Maria y Juana.

The practice of smoking it arrived in the US from the south during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Mexican laborers and soldiers carried it into the American south-west. Sailors brought it from Brazil and the Caribbean when they docked in New Orleans, where black jazz musicians adopted it.

In the last few years, the US state marijuana legalization experiments have grown into a multi-billion dollar industry. But while companies build out multi-million dollar grow houses and edibles factories, huge numbers of people continue to face serious consequences for possessing negligible quantities. After legalization in Colorado, arrests of black and Latino juveniles for illegal possession increased.

In 2016, there were almost 600,000 US marijuana arrests, more than for all violent crimes combined. The vast majority of those pot arrests were for low-level possession – and disproportionately affected minorities.

Statistics show different races use marijuana at roughly the same rate, but racial minorities are far more likely to face punishment. According to the American Civil Liberties Union, between 2001 and 2010, African Americans were arrested for marijuana possession at almost four times the rate of whites.

Relatively few of the 600,000 will serve extended prison sentences for marijuana-related offenses, but having a past conviction can still block access to housing, student loans and employment.

With legalization, some states and communities want to help those carrying minor cannabis convictions to be able to clear their record. Similarly, several cities and states are trying to create so-called equity programs to enable entrepreneurs from communities hit hardest by the war on drugs to join the industry.

But when the industry had the chance to take a stand against the racism of the past, it backed down.

After the 2016 election, Donald Trump nominated the then Alabama senator Jeff Sessions to be attorney general, the country’s top law enforcement official. While some Republicans, including Trump, have expressed a willingness to co-exist with marijuana, especially for medical purposes, Sessions remains an unreformed drug warrior. In 2016, he said: “Good people don’t smoke marijuana.” Instead of protesting his all-but-assured confirmation, the industry’s primary trade group, the National Cannabis Industry Association [NCIA], decided not to risk angering him.

The now attorney general has since reversed the more lenient Obama-era policies and ordered federal prosecutors to pursue the most serious charges they can, likely resulting in more drug offenders spending longer in prison.

For Sessions, it’s easier to come down hard on ordinary lawbreakers, who are disproportionately black and brown, than state-licensed cannabis business owners, who are overwhelmingly white.

The industry’s response has been to let him – while encouraging people to call the plant cannabis.

As with other symbols of past oppression, from the pink triangle to the n-word, there’s a powerful tradition of marginalized communities redeploying symbols of their oppression. It’s these communities – not businesses – who have the moral authority to decide if marijuana is a racist word which should be avoided or an important reminder of a more racist past."

Halperin, A. (2018, January 29). Marijuana: Is it time to stop using a word with racist roots? The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/jan/29/marijuana-name-cannabis-racism.

From The Atlantic's

"Reefer Madness" -by Eric Schlosser

Excerpt regarding origin of racist undertones regarding cannabis usage:

"The first American law pertaining to marijuana, passed by the Virginia Assembly in 1619, required every farmer to grow it. Hemp was deemed not only a valuable commodity but also a strategic necessity; its fibers were used to make sails and riggings, and its by-products were transformed into oakum for the caulking of wooden ships. Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Maryland eventually allowed hemp to be exchanged as legal tender, in order to stimulate its production and relieve Colonial money shortages. Although a number of the Founding Fathers, including George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, later grew hemp on their estates, there is no evidence that they were aware of the plant's psychoactive properties. The domestic production of hemp flourished, especially in Kentucky, until after the Civil War, when it was replaced by imports from Russia and by other domestic materials. In the latter half of the nineteenth century marijuana became a popular ingredient in patent medicines and was sold openly at pharmacies in one-ounce herbal packages and in alcohol-based tinctures as a cure for migraines, rheumatism, and insomnia.

The political upheaval in Mexico that culminated in the Revolution of 1910 led to a wave of Mexican immigration to states throughout the American Southwest. The prejudices and fears that greeted these peasant immigrants also extended to their traditional means of intoxication: smoking marijuana. Police officers in Texas claimed that marijuana incited violent crimes, aroused a "lust for blood," and gave its users "superhuman strength." Rumors spread that Mexicans were distributing this "killer weed" to unsuspecting American schoolchildren. Sailors and West Indian immigrants brought the practice of smoking marijuana to port cities along the Gulf of Mexico. In New Orleans newspaper articles associated the drug with African-Americans, jazz musicians, prostitutes, and underworld whites. "The Marijuana Menace," as sketched by anti-drug campaigners, was personified by inferior races and social deviants. In 1914 El Paso, Texas, enacted perhaps the first U.S. ordinance banning the sale or possession of marijuana; by 1931 twenty-nine states had outlawed marijuana, usually with little fanfare or debate. Amid the rise of anti-immigrant sentiment fueled by the Great Depression, public officials from the Southwest and from Louisiana petitioned the Treasury Department to outlaw marijuana. Their efforts were aided by a lurid propaganda campaign. "Murder Weed Found Up and Down Coast," one headline warned; "Deadly Marijuana Dope Plant Ready For Harvest That Means Enslavement of California Children." Harry J. Anslinger, the commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, at first doubted the seriousness of the problem and the need for federal legislation, but soon he pursued the goal of a nationwide marijuana prohibition with enormous gusto. In public appearances and radio broadcasts Anslinger asserted that the use of this "evil weed" led to killings, sex crimes, and insanity. He wrote sensational magazine articles with titles like "Marijuana: Assassin of Youth." In 1937 Congress passed the Marijuana Tax Act, effectively criminalizing the possession of marijuana throughout the United States. A week after it went into effect, a fifty-eight-year-old marijuana dealer named Samuel R. Caldwell became the first person convicted under the new statute. Although marijuana offenders had been treated leniently under state and local laws, Judge J. Foster Symes, of Denver, lectured Caldwell on the viciousness of marijuana and sentenced him to four hard years at Leavenworth Penitentiary."

Schlosser, E. (1994, August 1). Reefer madness. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1994/08/reefer-madness/303476/.